Go and read the excellent blog post from Cloudflare on their recent outage if you haven’t already.

I am not going to talk about most of it, just a few small points that especially interest me right now, which are definitely not the most important things from the outage point of view. This post got a bit long so I split it up, so this is part one.

Fuzz testing has been around for quite some time. American Fuzzy Lop was released in 2013, and was the first fuzzer to need very little configuration to find security issues. This paper on mutational fuzzing is a starting point if you are interested in the details of how this works. The basic idea is that you start with a valid input, and gradually mutate it, looking for “interesting” changes that change the path the code takes. This is often coverage guided, so that you attempt to cover all code paths by changing input data.

Fuzz testing is not the only tool in the space of automated security issue detection. There is traditional static analysis tooling, although it is generally not very efficient at finding most security issues, other than a few things like SQL injection that are often well covered. It tends to have a high false positive rate, and unlike fuzz testing will not give you a helpful test case. Of course there are many other things to consider in comprehensive security testing, this list of considerations is very useful. Another technique is automated variant analysis, taking an existing issue and finding other cases of the same issue, as done by platforms such as Semmle.

Fuzzing as a service is available too. Operationally fuzzing is not something you want to run in your CI pipeline, as it is not a test that finishes, it is something that you should run continuously 24⁄7 on the latest version of your code to find issues, as itstill takes a long time to find issues, and is randomised. Services include Fuzzbuzz a fairly new commercial service (with a free tier) who are very friendly, Microsoft Security Risk Detection and Google’s OSS-Fuzz for open source projects.

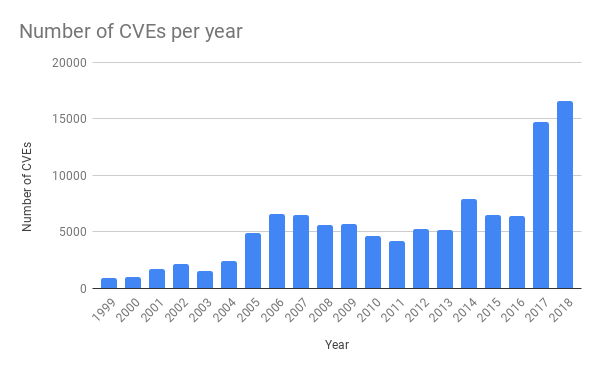

As Cloudflare commented “In the last few years we have seen a dramatic increase in vulnerabilities in common applications. This has happened due to the increased availability of software testing tools, like fuzzing for example.” Some numbers give an idea of the scale: as of January 2019, Google’s ClusterFuzz has found around 16,000 bugs in Chrome and around 11,000 bugs in over 160 open source projects integrated with OSS-Fuzz. We can see the knock on effect on the rate of CVEs being reported.

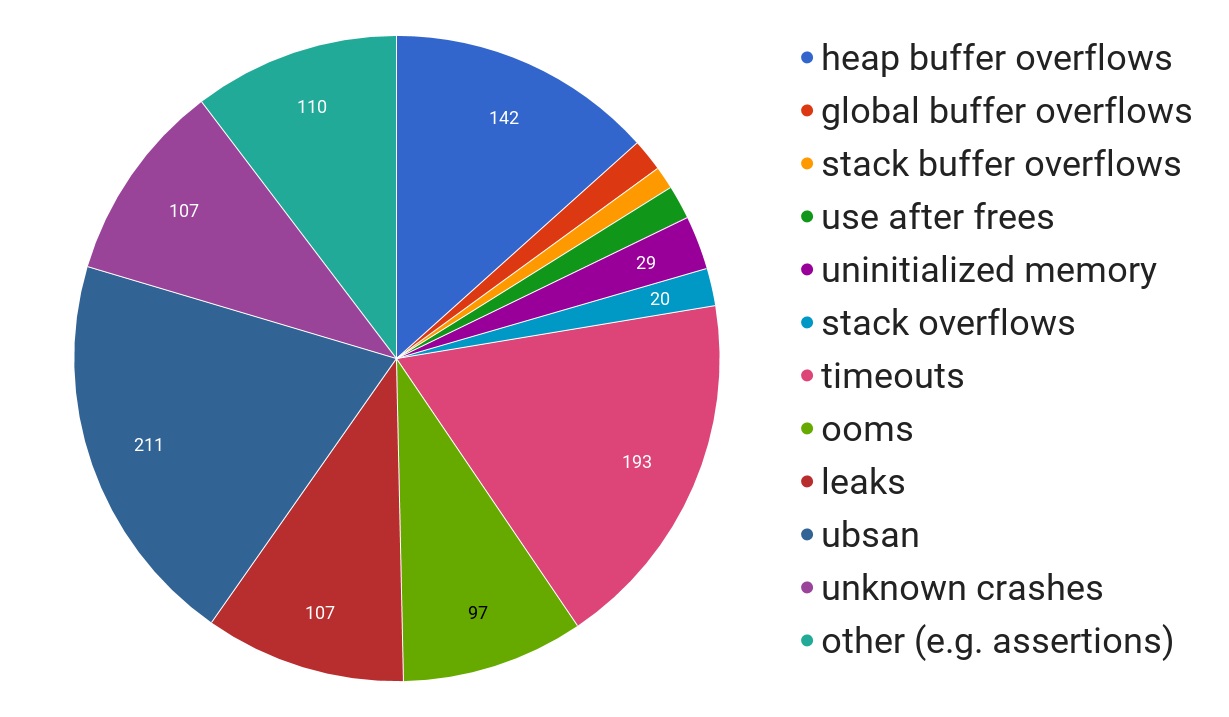

If we look at the kinds of issues found, data from a 2017 Google blog post the breakdown is interesting.

As you can see a very large proportion are buffer overflows, manual memory management issues like use after free, and the “ubsan“ category, which is all the stuff in C or C++ code that if you happen to write it the compiler can turn your program into hot garbage if it feels like it. Memory safety is still a major cause of errors, as you can see if you follow the @LazyFishBarrel twitter account. Note that the majority of projects are still not running comprehensive automated testing for these issues, and this problem is rapidly increasing. Note that there are two factors at play: first, memory errors are an easier target than many other sorts of errors to find with current tooling, but second there is a huge codebase that has huge numbers of these errors.

Microsoft Security Response Center also just released a blog post with some more numbers. While ostensibly about Microsoft’s gradually increasing coding in Rust, the important quote is that “~70% of the vulnerabilities Microsoft assigns a CVE each year continue to be memory safety issues”.

In my talk at Kubecon I touch on some of these issues with C (and to some extent C++) code. The majority of the significant issues found in the CNCF security audits were in C or C++ code, despite the fact there is not much of the is code in the reviewed projects.

Most of the C and C++ code that causes the majority of open source CVEs is shipped in Linux distributions. Linux distros are the de facto package manager for C code, and C++ to a lesser extent; neither of these langauges have developed their own language specific package management yet. From the Debian stats, of the billion or so lines of code, 43% is ANSI C and 24% is C++ which has many of the same problems in many codebases. So 670 million lines of code, in general without enough maintainers to deal with the existing and coming waves of security issues that fuzzing will find. This is the backdrop of increasing complaints about unfixed CVEs in Docker containers, where these tend to me more visible due to wider use of scanning tools.

Is it worth fuzzing safer languages such as Go and Rust? Yes, you will still find edge conditions, and potentially other cases such as race conditions, although the payoff will not be nearly as high. For C code it is absolutely essential, but bugs and security issues are found elsewhere. Oh and fuzzing is fun!

My view is that we are just at the beginning of this spike, and we will not just find all the issues and move on. Rather we will end up with the Linux distributions, which have this code will end up as toxic industrial waste areas, the Agbogbloshie of the C era. As the incumbents, no they will not rewrite it in Rust, instead smaller more nimble different types of competitor will outmanouvre the dinosaurs. Linux distros generally consider that most of their role is packaging not creation, with a few exceptions like Systemd; most of their engineering work is in the long term support business, which still pays well despite being increasingly out of step with how non-C software is used, and how cloud deployments work, where updating software is part of normal life, and five or ten year software lifetimes without updates are not the target. We are not going to see the Linux distros work on solving this issue.

Is this code exploitable? Almost certainly yes with sufficient effort. We discussed Thomas Dulien’s paper Weird machines, exploitability, and provable unexploitability at the Säntis Systems Summit recently, I highly recommend it if you are interested in exploitability. But overall, proving code is not exploitable is in general not going to be possible, and attackers always have the advantage. Sure they will pick the easiest things first, but most attacks are automated now and attacking scales well. Security is risk management, but with memory safety being a relatively easy exploit in many cases, it is a high risk. Obviously not all this code is exposed to attackers via network or attacker supplied data, especially in containerised environments, but some is, and you will spend increasing amounts of time working out what is a risk. The sheer volume of security issues just makes risk management more difficult.

If you are a die hard C hacker and want to remain one, the last bastion of C is

of course OpenBSD. Throw up the pledge barricades, remove anything you can,

keep reviewing. That is the only heroic path left.

In the short term, start to explore and invest in ways to replace every legacy C dependency you are currently using. Write a deprecation roadmap. Cut down your dependencies on Linux distributions. Shift to memory safe languages everywhere, and if you use C++ make sure you only use the safer subset. Look to smaller more nimble Linux distributions that start shipping memory safe code; although the moves here have been slow so far, you only need a little as once distros stop having to be C package managers they can do a better job of being minimal userspaces. There isn’t much code you really need to run modern applications that themselves do not have many C dependencies, as implementations like LinuxKit show. If you just sit on top of the kernel, using its ABI stability guarantees there is little you need to do other than a little configuration; well other than worry about the bugs in a kernel written in … C.

Memory unsafe languages are not going to get better, or safe. It is time to move on.